by Human Rights’ Watch‘s Minky Worden

In this excellent piece published in Newsweek, Human Rights Watch’s Director of Global Initiatives explains why FIFA’s latest promise is only masquerading as progress.

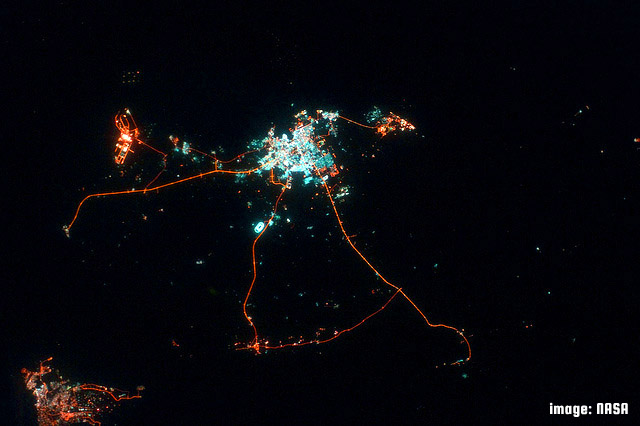

With six years to go until the opening whistle of the 2022 World Cup, preparations are moving at a feverish pace here in Qatar and will soon reach peak construction.

With a dozen stadiums to be constructed or revamped, Qatar’s World Cup, with an estimated $200 billion in infrastructure, will be the most expensive ever. The human cost is already the steepest ever, and unless FIFA and Qatar take urgent steps to reform now, risks climbing even higher.

“By announcing a new body to protect workers, FIFA gets to look like they’re taking the issue seriously—without having to put any pressure on the Qataris to actually take it seriously.”

The problem is that the stadiums, transit and infrastructure for the World Cup are being built not by the few hundred thousand citizens of this tiny but oil-wealthy emirate, but by the one million migrant workers who came here to discover that they are working in unsafe conditions—and that they can’t leave without the approval of their employers.

Unless the situation changes quickly, the 2022 World Cup will send a grim message for the millions of fans who attend, the more than a billion expected to watch and the corporate sponsors who invest in the World Cup: a football tournament is more important than the lives of the workers, largely from South Asian countries such as Nepal, India and Bangladesh, who are building stadiums and infrastructure.

Long hours, poor working conditions, and the country’s extreme heat provide the context for a problematic pattern of hundreds of fatalities attributed to “sudden death” or cardiac arrests, which the authorities have refused to investigate. In March, a report by Amnesty International—the organization’s third on this topic since 2013—called out FIFA’s “shocking indifference” to widespread abuses, including squalid living conditions.

Migrants in construction toil in heat up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit, in a workweek that is usually six days long, and sometimes seven. Workers typically pay exorbitant recruitment fees, and employers regularly take control of their passports when they arrive in Qatar. Many migrant workers say that their employers fail to pay their wages on time or in full.

Qatar’s kafala, or sponsorship, system ties the legal residence of migrant workers to their employer. The system also requires foreign workers to obtain exit permits from their sponsors. This gives employers the power to arbitrarily block their employees from leaving Qatar and returning to their home country—and makes it impossible for workers to complain of abuse without fear of reprisal. Qatar has yet to enact meaningful reforms to this labor system despite pledges to do so and years of sustained criticism.

As one of his last acts as FIFA president—and doubtless to help repair the reputational harm from the group’s corruption scandal—Sepp Blatter hired Harvard’s John Ruggie to put in place a policy on human rights. Mr. Ruggie is the architect of the U.N.’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which require companies to take effective steps to avoid, mitigate and remedy human rights abuses linked to their operations. Ruggie issued a bluntly worded report in April that said: “The purpose of identifying human rights risks is to do something about them,” and attracted headlines by saying FIFA should “consider suspending or terminating” its relationship with World Cup hosts who fail to fix abuses.

In a sign international pressure is working, FIFA just launched a body to “oversee the treatment of workers on Qatar’s World Cup stadiums.”

But the problem in Qatar and on World Cup construction isn’t a lack of oversight. Stadium workers are already subject to supplementary protection on top of the local labor law, so this will be a third tier of protection. The problem remains a lack of political will to implement reforms and make protections fully effective. The greatest contribution FIFA can make is to help generate that political will by applying genuine pressure on the Qataris.

Unfortunately, FIFA’s new leader Gianni Infantino did precisely the opposite when visiting the country for the first time in late April. “I can’t see any reason why they won’t host 2022. They will host it,” Infantino said in Doha. By announcing a new body to protect workers, FIFA gets to look like they’re taking the issue seriously—without having to put any pressure on the Qataris to actually take it seriously…